Designed by the legendary Harley Earl, the Buick Y-Job was the first ever concept car. Car Design News delves into the back story of this landmark car

By 1938, the Great Depression had been underway for almost a decade in the United States, and the nation was still struggling to emerge from the terrible financial crisis. The automobile industry, which had been ripe for a shakeout of the weaker players, lost many storied marques. Those that remained fought for survival and dominance, often with limited resources.

Of these remaining players, General Motors was proving to be the strongest, having passed the struggling Ford in the late 1920s. GM’s combination of industrial might, brand identity and styling, plus superior marketing, positioned the company to ride out the hard times.

In terms of design and brand identity, two GM figures had a larger than life presence in the auto industry, Alfred P. Sloan, longtime President and CEO, who was responsible for assembling the industrial giant and Harley Earl, his Director of Art and Colour, the styling arm of General Motors. Sloan recognized early on the power of design, and in 1927 hired Harley Earl, whose family had a successful coachbuilding business in Hollywood.

In the following decade, Earl would create the modern automotive styling department, one that Ford, Chrysler and others would imitate. All the processes of design – the sketching styles, the design explorations, the modelling – would emerge from Earl’s studios in these years, creating a profession that transcended coachbuilding and would be congruent with the modern industrial enterprise.

Earl could – and did – drive around in any GM car he wished, proud of what he considered the best styling in the industry. But a few cars had caught Earl’s attention, and although he would never admit it, he sensed that new styling trends were emerging. The 1937 Lincoln Zephyr and 1938 Sharknose Graham were two beautifully designed Streamlined Moderne cars that made others in the industry look ancient by comparison.

The car would become a symbol of Harley Earl work to come. He noted that the public “likes the oblong more than the square,” and that low and long were the future

Also disturbing, perhaps more so for Earl, was that other auto executives, Edsel Ford and design chief Ed Macauley of Packard, were driving around Detroit in custom built cars, including dramatic boat-tailed speedsters. Earl felt he needed a custom car too, one that reflected his personal and corporate power and influence.

Earl approached the Director of Buick, Harlow Curtice, about building a personal car that would be a halo car for the Buick brand that Earl intended to use as a daily driver. Curtis and Earl had worked closely to rescue Buick during the depression. With a new organisational structure and a new car, the division, which had seen a 70% decline in sales, rebounded.

The car Earl wanted he would later describe to his design staff as “a little semi-sports car, a kind of convertible.” But soon the design conflated to a boat-tail speedster similar to those Ford and Macauley drove. Curtice, Alfred Sloan, and Earl also brainstormed about advanced features that could be built into the car. Curtice hoped to present the vehicle as ‘The Car of the Future’. Earl was only too happy to play along with this scenario, as it increased the likelihood of generous funding.

Indeed, Curtice did secure the funding and lent Earl an engineer, Charlie Chayne, to work with the design staff, led by George Snyder, in a separate, locked studio for the next eighteen months. The project soon became known as “the Y Project”. Officially it did not belong to any GM brand, but everyone considered it a Buick as it was built on a Buick foundation with Buick money, Buick designers, and Buick engineers.

There are a number of theories about how it got the name (see video below), but it seemed a nod to all the secret “X” projects that were constantly starting and stopping around the automobile and aircraft industries. Earl referred to it as his “Y-job”, and the name stuck. The process of designing and building the unusual car was so gruelling that members of the team began calling it the “Why Job”…

Finally, the car was completed in late 1938. It had cost $50,000 ($902,000, or £690,000, or €791,000 in today’s money) to produce – a fantastic sum that only GM could possibly afford.

The grille was heavily influenced by Mercedes Silver Arrow racing cars

But what a result: a low, long, wide and flamboyant convertible, almost 17 feet (5300mm) long but only 58 inches (1473 mm) high. The car would become a symbol of Harley Earl work to come. He noted that the public “likes the oblong more than the square,” and that low and long were the future.

Running boards were consigned to history with the Y-Job. The sleek fenders were low and horizontal, and the car sat on 13-inch wheels (small even for the time) with whitewall tires. Chrome trim across the fenders added to the visual length and kept the eye moving.

The front end showed the influence of a number of cars. The hidden headlights, a GM first, were integrated into the fender and were influenced by the Cord 812, a car Earl admired, secretly. The grille was heavily influenced by Mercedes Silver Arrow racing cars. Again, the horizontal grille with ‘waterfall’ vertical bars was a GM first, but became a Buick styling staple in the 1950s.

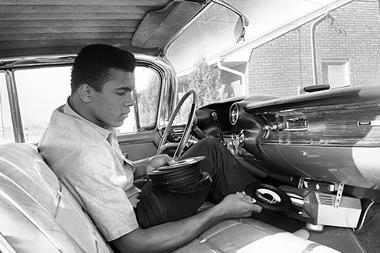

The interior was a two-seater, with a folding fabric roof that was hidden under the rear deck. Earl loved the looks of the car with the top down and often drove it even in light rain or snow. Earl was so tall that his head stuck up above the top of the windscreen.

The Y-Job was shown at the 1939 New York Auto Show, but interestingly, not at the World’s Fair that year. Of course, GM had more expansive and futuristic plans for the Fair with the Pontiac Ghost. The Y-Job soon became Earl’s daily driver, a car he loved to show off driving along Lake Shore Drive and through the posh neighborhoods of Grosse Pointe and Farmington Hills.

The Second World War would mean garaging the Y-Job, but after the war, it could be seen again with Earl at the wheel. Change was again in the air, however, as Curtice suggested a new halo car for Buick and a program for two new concepts soon began. But these programs were so extensive that they took several years, so Earl got plenty of miles on the Y-Job.

It would only be surpassed by the even more flamboyant Le Sabre Concept of 1951, which historian Michael Lamm has called the “most significant car in history

In 1951, the Y-Job was retired, toured a bit, and ended up (ironically) at the Henry Ford Museum in Detroit. General Motors eventually bought it back in 1993, added it to the heritage collection, and restored it to running condition.

Harley Earl went on to become the first Vice President of Design at GM and ruled the design world until his retirement in 1958. Harlow Curtice also had an enormously successful career at Buick and was promoted to President of General Motors in 1953, where he served until his retirement in 1958.

The Y Job is actually better known in retrospect than during its heyday in the late 1930s. A number of events overshadowed the car at the time, but its influence remained strong within the design community through World War II and afterwards.

It would only be surpassed by the even more flamboyant Le Sabre Concept of 1951, which historian Michael Lamm has called the “most significant car in history”. It was the car that defined American automotive design in the 1950s and a worthy successor to the Y-job, and of course was Earl’s daily driver for several years – a rolling prediction of a jet-powered tail-finned automotive future.

But it would not have been possible without the Y-job, which was, in a sense, the car that saw the future and created a space for a new kind of car, one that was free to explore ideas and anticipate design trends.